Canoeing Glen Affric

Jamie Dakota

What follows is a trip report, a reminiscence of sorts covering a short canoe trip myself and my colleague Max took to Glen Affric at the start of January 2019. I’ve tied my field notes together with a few captions from Max of the two nights we spent under winters Orion, in some of the finest country I’d had the pleasure to journey through.

The day is late, and our plan to paddle the length of the Loch before nightfall is looking less sensible in the conditions. We are solo on this trip, reliant on each other and the small outfit we’d brought in the single canoe. Having taken ten hours to drive to Glen Affric we had a short portage from the carpark to the water’s edge, and with the canoe loaded we settle onto the black surface of the Loch with just a short amount of daylight left to us. Taking a quick bearing from the map and assessing the wind direction we start out, paddles to the water and the world seems to expand in front of us. The wind was gusting and full of sleet as it moved across the valley, with just half an hour of paddling behind us though we had a decision to make already: continue with a plan made days before in the comfort of home or make for the far shore closer at hand and look for a spot to pitch camp for the night. This was after all a trip to be enjoyed, not one of endurance but one of communion with Nature.

There’s a bay on the far-side just a kilometre away, windswept yet high in the water as the shallow Loch drains into the river in the east. Mud, ancient trees cut boldly, and the freezing waters edge form the bay. Magnificent. From the water the miles we could see in all directions were closing in, January is of short days and the cold falling down off hills presses us.

Decision made, we make for the shore. And of course we knew, with a plan in hand, the morale spikes and we’re motivated once more with the drive to see it through. I look to my hands, “Fingers, bring me the far shore”. And watch as I pull a mountain closer across the water. We chase wind blown leaves over the waves, all the while the valley to our right throws rain and frozen breathe down from the heights. We paddle over to the wide berth, looking for a space that feels welcoming. We land on the silty shore.

After walking along the rocky edge of the Loch we discover why this stretch of Loch Beinn a Mheadhoin was uncamped: steep falls of sphagnum bog cover uneven ground and years of fallen trees. In high water there’d be little in between the moss and the waters edge, as it was we were left with a broad muddy bank to suck at our feet. This was no place for a bivouac. We’d made the decision in plenty of time through, a wisdom proved in hindsight, if we’d travelled into dark to setup down the Loch to find similar conditions we’d be wretched to wander in freezing rain and the mud. We’d time yet to look further, and found within a few minutes of exploration a small island in the mud, our refuge as the wind picked up.

What would be an Island on high water days as the Loch drank from mountain rains was for us a castle in the mud banks, rising perhaps two meters above the surrounding flats. This natural crannog of Rock lofted Heather, Birch, and Pine on its shoulder, and had at some point sheltered other travellers as their stone fire-circle remained. We had the wind, gusting but consistent from the Gates of Affric to the West offering us a challenge, we’d be allowed to make camp on this Rock Crannog if we could hold up to the breath of the valley.

In setting camp there are always to same routines to move through: Fire, water, shelter, to be arranged from out of the wild with gear from our outfit. The order though, with just two travellers, flexes depending on many factors. Tonight, we knew the rain would continue and we were exposed somewhat being upon our heathered mount. And the dark would fall fast, we’d already seen the sun slide behind Mullach Fraoch-Choire. The plan would be this then, the stowed gear in the canoe should be carried to the camp, the canoe herself would be brought up to share the eventual firelight and in her lea we could sit out of the wind. A tarp should be pitched above the fire circle, to throw the rain and circulate what warmth our fire might bring. All this was done in minutes, our camp already providing respite from the moods of Affric that evening.

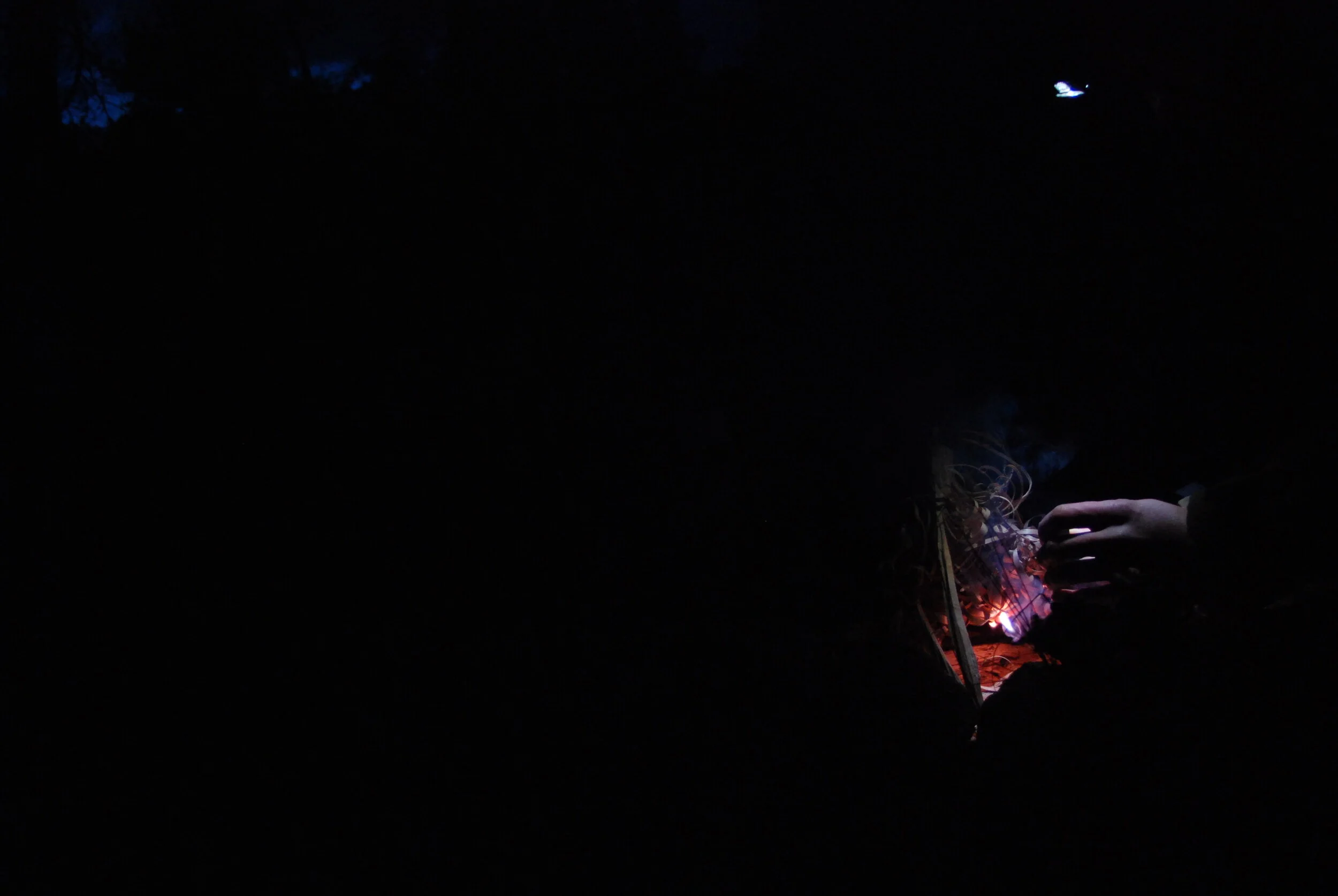

With everything secured we’d use the daylight we had left to collect wood, an old Scots Pine left leaning against Alder as it died, and bring it to the camp. Swiftly we set about processing for now what we needed, Axe and Bucksaw drawn from canvas, we work in quiet unison, sawn, split and feathered we retrieved from the core of the old pine a spiralled growth in captured sunlight, the stored energy of years in the Valley. The camp fire within a past travellers circle, rafted, laid and struck with Firesteel shards drew from that ember we carry deep within a flame amongst the featherstick curls. We allow a few moments to watch the heart of our fire take hold, and whilst the kettle sits close-to filled with the last litres of what water we had carried with us we set about pitching our beds for the night.

“As I progress with my studies in Bushcraft I know that some of my skills I’ve not yet used in a situation that is truly vital on an expedition level. Feather sticks.

As we set out on out first part of the journey, the surrounding mountains decided to throw everything they could at us. Within a split second heavy headwinds and severe sleet created sub zero conditions whilst out on the water.

We decided to make the correct decision and abandon the journey for that evening, so we found a suitable camp in which time the light was now fading.

First thing was string up a tarp so we could gather our thoughts. We knew that next we needed a fire as soon as possible. We gathered dead standing and birch bark from our surroundings, everything was saturated including the birch bark. This was because of the lichens holding moisture against the tree.

After splitting the wood down into splints we failed to get a fire going on the first attempt with matches, this was due to effects of temperature and the damp.

Working together we both prepared a great quantity of feathers.

With one strike our Feathers caught and dried the sopping wood out which then caught alight.

The main lesson I gained was: In those moments when your cold, tired and frustrated, Patience and knowledge are key to succeeding.

Take your time and prepare everything to the best of your ability, only then will your chances at succeeding greatly improve.” Max’s journal.

I’d be sleeping in the Robens Starlight 2 tonight, my favourite little tent. Max was under a tarp with a bivi-bag. We look at what space we have on little firelight emblazoned island in the dark, a flat space on the windward side and a shelf behind a bank of heather. I’d take the windward side given the enclosed nature of the tent, Max the shelf. We set to, as the kettle begins to steam, and within a few minutes we were arranged for the night, we’d even managed to spare my personal tarp for use as a further windbreak to meet the canoe, sheltering us from the wind. The rain continued to fall.

In winter you begin to feel the true nature of your life, burning briefly in the cold and the true value of that furnace within. It would be easy now, having drunk a half litre of tea to settle down for the night and retire to the sleeping bag, but we had a feast to prepare and water to filter.

We set about the tasks of camp, I introduce Max to one of the modern water filters I use while travelling then prepare a simple tripod to hang our cooking pot over the fire. This is my favourite means of setting the campfire for cooking while traveling as it’s fast and requires little to no carving work. Having brought a length of spruce root we’d harvested a couple of week previously I tied the whole arrangement together in just a couple of minutes, a few moments more and the withied birch hook suspends a pot over the flames ready for the food. A short while later the bottles are filled with water and the island is filled with the smell of vegetable haggis and potatoes.

We retire for the night, having filled flasks with boiling water and tidied our cooking gear. We also prepared some key pieces of kindling ready for the morning, some choice pieces of straight dry pine we left tucked under the canoe and off the ground to keep dry. These we could split and feather in the morning ready for relighting the fire for breakfast, in this way the driest wood at the core stays sealed away from the damp air and would give us the best chance of lighting the fire after what was looking to be a rain soaked night.

I wake this morning to a chill. I’m somewhat surprised, I expected the morning to be damp but above zero temps given the evening of rain. I get dressed in the tent as always, take a few swigs of coffee from the small flask and step out. It’s still dark, being just before 7am, but the change overnight is obvious. The wind and rain had passed sometime in the night, leaving behind a still and cold atmosphere. It feels like -5C this morning, everything that was wet as we went to bed is now encased in ice. The tarps look like permanent frosted roofs, inflexible and crisp. The air is dry. A few more swigs of coffee while I take a few photos, I start to wake up a little more and I hear Max waking from his bivi. We want to get away swiftly this morning, we’ve only a short time in the Valley and we want to make the most of it. So in the lessening dark we rekindle the fire, having split and feathered those choice boughs of pine, feathersticks with practice are quickly made. This morning I give Max the challenge of lighting these with a single match, and establishing the fire. Given the ice and cold, he does an excellent job while I take the photos with only a momentary stall as the flames struggle to move from the feathers to the split kindling. I note that we could have prepared another dozen of the thinnest splints and this would have negated the stall, lessons learned in the wild are invaluable experiences that can be brought to our repertoire during courses.

As we took turns stirring the porridge we’d each opened out our sleeping gear on a guy-line to air out, and now that breakfast is finished we pack away of kit. An often overlooked little niche of campcraft, but the steady expedience with which you can learn to pack away your gear goes a long way on trips such as this, it is often here where you most see a difference between a practiced outdoors-person and someone new to wilderness travel. As all my sleeping kit is now packed I take down my tent, which as the rain froze in place over the whole tent it now stands erect even after I remove the pegs! I fold it like card to pack it away. We move on to packing the last of our shared gear away, the cooking pots, tools, food are all stored away. Then the main tarp comes down: Tarp lines, stiff from the ice, hold fast to the algaed Birch even after the knots are untied; as resistant to move today as I am. The still cold of the air draws at my feet, my hands, as I move to get the flycamp undone and the canoe underway.

The mud is frozen solid this morning, so the short 30 metre walk to the waters edges is easier than last night. The canoe loaded we start out. As we’d had a shorter opportunity on the water yesterday we change our plans to the backup route, and decide to stay in Loch Beinn a Mheadhoin for the whole trip rather than rush this Loch to get around to Loch Affric as well. We just had an excuse now to come back sometime to see the other Loch! So with quick message home to say we’re on the backup plan we place paddle stroke after paddle stroke into the dark waters and move East between the mountains.

We have the whole day to play with, as the Loch has a few little islands to explore standing steeply out of the water. We track deer on one island, as the water level is low there are actually muddy land bridges from the island to the shore and the tracks tell a story: we’ll not see these deer today here on the island, they’ll be wiping mud from their cloven hooves amongst the mosses on the mainland.

As the sun reaches its zenith we see a another canoe on the water up head, a solo paddler moves across the space between us and the nearest shore. We meet Mike on the waters in the middle of the Loch, he tells us he comes here every year for a solo canoe camp and we shoot the breeze for a while. As fine a gent as you could hope to meet, he gives us some advice on good camping spot and we suggest we could all meet up later on by the fire for a drink. We watch as Mike paddles skillfully back the way we came, and we continue east to the end of the Loch.

The very east of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin hosts a tight collection of steep islands and narrow lands that form something of an archipelago, perfect adventure land with places to climb high above the water, places to camp, places to watch the world. Paddling as we were we have to pass the island chain and come around the far side to enter the bay; and on this stretch of the Loch a man made tunnel pumps water from another Loch on the other side of a mountains into ours, which in turn is dam released down into Loch Ness. The result of this water coming into the Loch from the submerged tunnel is a gentle rising of currents that swirl the water and distort the surface, the canoe moves slightly differently here as the currents tease it in all directions. The effect is subtle, but currents should not be taken lightly and we take extra care to stay steady in the boat.

We to come a tight pass in the water, high rock rises to meet heather and pine on either side give us a lane between and suddenly every paddle stroke, dropping water on the reach forward, echoes electric in the crystal air. Here the strata recorded in rock meets the water’s edge to create geometries that crisscross in reflection. We pull the paddles out of the water and let the ripples arc out to allow the surface to settle, in places it’s hard to tell now where the rock meets the water.

It’s getting on for lunch so we look for a place to stop as we round the head of the bay, a place so sheltered from the wind and winters sun that the surface of the Loch has started to freeze in areas. Paper thin sheets of patchwork ice form in front of us, and just as the child in me still treads on frozen puddles we try cutting through one of these ice sheets with the canoe. The crunch as the ice breaks on the bow sets the hairs on my neck on end, it’s haunting and loud in the silence, the sensation of Nature all around watching feels like a Grandparent looking on an errant child testing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour. It’s a that moment the canoe hits a thicker portion of ice, turning 20 degrees to the left, and we know we’ve found the boundary. The outdoors can be a space for fun and play, but you must also by willing to listen when the little voice inside whispers ‘danger’.

We leave the ice patch and pull the canoe up to an island to find a spot for lunch, when we see it: the Old Pine, swayed with old man’s beard, atop the stone hill rising 20 metre above the water. That’s a place to stop for a while if ever I’ve seen one. We leave most of our gear in the canoe by the shore and climb the steep side of the island with just a essentials: a simple belt kit complete with pouch, a Brewkit stove and coffee, and some flat breads and fillings for the meal. Sat under the grand Scots pine, stove steaming, we watch to the West as cold air slowly fills the valley. The old man’s beard drifting in the breeze. One of the most special places I’ve ever sat.

Once again the short winter day was closing in, the mountains to the west shortening further what daylight might be available to us. So we start to look for a place to camp, we know from the map the sweeping bay enclosed on all but one side might make for a sheltered camp, as we approach however we see the further down the bay we go the more frozen it is. The cove we were aiming towards is now entirely frozen with a thickening layer of ice, paddling into this would be very risky so we pull to the side and continue on foot looking for a spot. We don’t mind portaging the canoe and gear but if we can find a more convenient place then all the better. We round a corner and see a sandy little beach, much to our surprise, raised slightly of a shelf that butts up against the rocky side of the island. As we’d planned to setup a voyageur style camp that night we could think of no better an area than this: south facing, firewood close by, flat and dry, perfect! And so for the second time on Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin we get to work setting up camp.

Unlike the evening before we had clear skies and not a breath of wind moving around us, so we are more relaxed this afternoon. I take time to go through with Max the process of setting up the canoe for sleeping underneath, he’ll be helping on our next canoe trip with clients to set up these shelters so we look in detail at the method. The canoe rolled onto its side is propped up, in this instance with a stout Y stick driven deeply into the sand to hold against the yoke. Convenient rocks keep the bow and stern from moving around, and a tarp pitched over the hull and lofted between two paddles provides our roof, held taut with a central paddle from the middle. With the shelter for the night we split up to share the jobs and within a half hour from landing we’ve got a kettle over the fire and are sitting down to wait for the boil as the evening gets dark.

As the light begins to fade we feel the temperature falling, seeming to drop out from around us leaving a heavy and empty cold. The importance of the fire becomes very clear, and the silence is broken only by the ice cracking against the rocks that stick up from the water. That Pinewood fire, worked for with diligence and patience while the cold bit at the hands and face, warmed from outside and within. The effect of that incandescent craft on the mind of a weary traveler in a cold landscape is just as profound as the effect of its radiant heat soaking through clothing to warm the body. Thoughts go the night, to preparations for sleeping comfortably and to whether we remembered to pack the rum for an extra special hot chocolate before turning in.

We sit, filled with a hot meal as Mike joins us. He’d paddled the length of the Loch and back during the day and had set up his hammock and tarp just a short way from us, he sits with us with the relaxed air of a man well travelled and comfortable outdoors. “Industrious” he calls us, after witnessing our swift labours to sort our traditional camp and we spend most of the evening engaged in conversation of the kind only found when out far from home, as Orion strides across the sky following the Bull. As we talk we spend a little time making bannock for tomorrow’s breakfast, we need to be off the Loch by lunchtime and wanting to have time to paddle a little and explore in the morning, we decided we’d forgo a fire in the morning opting instead to brew up with the Alpkit stove and eat the way-bread to speed up the early routine. We drink our rum-hot-chocolate and smell the bannock baking in the billy pot as the ice thickens on the water, so thick now that a fist sized stone thrown into the air fails to break though.

The night under Orion was one of the finest nights I’ve spend outdoors, the temperature dropped to -10C and we woke to this at around 7am. We only know this having spoken to some locals on our drive out after the trip, who’d said it had dropped at -12C in the village so estimated -10C at the Loch. All we knew during the night was that it was cold, colder than we’d had the night before, and colder than we might have thought given the recent and estimated weather forecasts.

In preparing for that night I made a few arrangements to augment my sleeping bag which might be of interest, many little tips I’d picked up over the years from a wide selection of sources. From the ground up then: I always carry a piece of closed-cell foam mat in my rucksack, mostly to sit on at lunch stops when it’s wet or cold, it’s long enough to cover my torso when laid on the ground. We’d laid a groundsheet under the canoe shelter to keep us off the sand, the roll mat section lays down on top of this. If I hadn’t had this extra layer, the heather growing on the island could have been quickly harvested to create a rough matting to serve the same purpose.

Then my bivi bag gets rolled out, into this I set my thermarest to inflate. I carry a ¾ length thermarest for weight and small packsize, perhaps not necessary savings when you’ve the canoe to carry your gear, but I’m not in a position to afford a different thermarest for every type of trip and in all honesty this mat serves me well. To augment this though, as my feet off the mat when sleeping, I lay my BA under my feet and calves. Under my head I make a big pillow from my kneeling mat from the canoe, spare clothes and a dry sack.

My sleeping bag is a down bag rated to a comfort of -2C, I loft this bag thoroughly before getting into it. On this occasion I reason that the bag will not be sufficient to keep me warm all night alone, and I also question whether my bivi will freeze on the inside with condensation. To mitigate these two issues, I unzip the half length zip on the bivi bag to allow greater breathability and then I lay a synthetic belay jacket over me and the sleeping bag as an extra layer of air-trapping insulation. Within the bag I wear a merino long-sleeve base-layer and long-johns, thick woolen sock, a warm wooly hat and merino neck buff, following the teachings the legendary Mors Kochanski “sleep with lots under you, lots over you, but little on you”.

I add to the sleeping gear a plastic water bottle filled with hot water, which I tuck between my thighs when it’s really cold. The femoral arteries are close to the surface here, so a large blood flow can be warmed by the bottle. I had also taken the measure of filling a flask with hot water that I could use to refill the bottle in the night should I be really desperate. As it was I needn't have bothered, but it meant I had hot water in the morning to make a coffee without having to get out of bed!

All the steps combined worked perfectly, I slept warm and well, waking to heavy frost on the outside of my bivi bag and the outside of the belay jacket, with everything dry and warm within. It’s worth noting in preparing for this trip I knew I had all these options in hand should I need them, not to mention the tent and the fire for emergencies, to augment my sleeping bag. If I had been in any doubt I would have taken a bigger sleeping bag, but it was a great opportunity the try these techniques in the real world.

““My mind started to stir as freezing air moved its way into my lungs. It was minus ten as a sudden surge of adrenaline, and a sense of urgency. Gave me the will and determination to break the ice from my Bivi and pull myself out from my cosy cocoon of which was my sleeping bag.

After the coffee had been made from our flasks I could take in all the sight and sounds surround us.

We had entered and icy wonderland that even the birds had not yet risen from.

The only sounds we could hear where of the deep creeks and cracks roaring from the icy loch. We broke the bannock for breakfast and prepared for our next step of the journey.

I truly felt what freedom felt like that morning.””

We wake to the cold, I know it’s been a frosty one before I even open my eyes because although I’m not cold I can feel the air as I breathe. The mountain air, which had been quietly kissing my cheeks as I fell asleep must have gotten a little frisky in the night, and stuck it’s tongue down my throat...I wake up coarse and unable to speak at first. That flask of hot water makes a welcome coffee before I leave the comfort of my sleeping bag, and fires me up ready to break camp.

We dismantle the camp, everything packed into its place, and reload the canoe ready to make way. Mike joins us for breakfast, his firebox stove burning split kindling makes for a welcome warm of the hands and crucially allows us to defrost the bannock...I’ll make sure to sleep with it inside the sleeping bag next time!

Once again we’re treated to a clear and calm morning, the valley sides reflected in the waters look majestic and grand. We can’t help but spend a few minutes in turn soloing the canoe around the shore. We’d had to portage the canoe and gear a short way across the island bay to rejoin the main waters of Loch Beinn a’ Mheadhoin, given that the bay was still frozen solid. We say our goodbyes to Mike and set our canoe now westward back towards the waiting car where we’d started this short trip.

Almost immediately we see towards the high Gates of Affric a new weather front dropping into the valley. We estimate we’ve got about 2 hours before we’re hit by snow and possible winds, and make steady our pace across the waters. For now though we’re enjoying warm winter sun and still waters, we pass the odd patch of tissue ice as we cut through with the bow. We make just one stop on the way back, a small island we’d hadn’t stopped at on the previous day, to take a few final photos and answer nature’s call. There’s a icy bay here on the lea side of the little island, much like the one we were aiming for down the Loch. I stone break the ice, splinters of frost crack fractals across the air. A destructive act perhaps, but crystalised in a moment of impulse no less attractive than that a Deer must experience when looking to an island across cold flint water. In breaking the ice with my rock I find it thick here, too thick to break with a paddle and the canoe and I realise, to try and cut through the ice today as we had yesterday would mean a certain swim. A lesson just a stone’s throw away. We’d need to look for a different place to finish our trip, we couldn’t risk the ice being thick there too.

In bringing the trip to a close, as snow falls on the shoulders, we find an easy spot to land not far from where we’d launched in the beginning. We float a while on the Loch, soaking in the last moments of the magical place. The snow falls to the water, as the reflections rise from the depths to meet each perfect flake. Every rippled meeting of snow on the surface, echoed a thousands of times across the Loch every moment, moves the valley reflected. My mind in these moments is quiet, the words of this article formed in retrospect in the warmth of my house, but out there on the water I have few thoughts. Out there I leave my mind and find my soul.

This article was originally published in The Bushcraft Journal issue 25, I highly recommend subscribing to this incredible resource.

We now lead a trip to Glen Affric, in the summer, each year.

Thank you for reading, please free feel to let me know what you thought of the article in the comments below.

All the best

JD